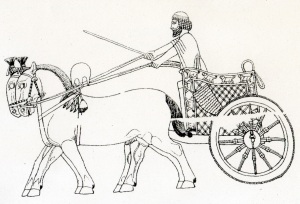

caption id=”attachment_288″ align=”alignnone” width=”300″] Persian horseman depicted on a felt saddlecloth from Pazyrik, fifth century BCE[/caption]

Persian horseman depicted on a felt saddlecloth from Pazyrik, fifth century BCE[/caption]

At the moment I’m co-authoring (with my friend and colleague Dr Sian Lewis of St Andrews University) a book about animals in the ancient world. Right now, I’m writing about horses in the ancient Near East, so I thought I’d take this opportunity to write a few brief words about the importance of the horse in Achaemenid society.

For a nomadic people like the Persians, the horse had a significant practical and symbolic purpose and the importance of horses among the Iranian nobility is evidenced by the fact that many of them bore names compounded with the Old Persian word aspa – ‘horse’. Several of Darius I’s inscriptions note that Persia was a land containing both good men and good horses (DZe §1; DPd §2) and Herodotus famously states that Persian fathers were intent on teaching their sons ‘to ride, to draw the bow, and to speak the truth’ (1. 136; see also Strabo 15. 3.18). The premium Persian horses were bred in the alfalfa-rich plains of Media, and it was here that the main royal stud farms were located (Polybius 10.70). Most prized of all were those steeds bred on the plains of Nisaea near Ecbatana and Bisitun, and Nisaean horses became celebrated for their magnificence, fine proportions, and swiftness (Herodotus 3. 106, 7. 40; Aristotle, History of Animals 9. 50.30). Nisaea is said to have sustained 160,000 horses (Diodorus 17.110), although stiff competition came from Media and Armenia which were also used for breeding good steeds (Strabo, Geography 11. 13.7; 11. 13.8, 14.9), as were the provinces of Babylonia (where one satrap possessed 800 stallions and 16,000 mares; Herodotus 1. 192), Cilicia (which provided an annual tribute of 360 white horses; Herodotus 3. 90), Chorasmia, Bactria, Sogdiana, and lands of the Saka which provided the Empire with its cavalry (Tuplin 2001b for a full discussion). The Persepolis texts often speak of horses (as well as mules and donkeys), usually in the context of their food provisions and maintenance but also as property of the king or members of his family. Here are some examples:

Tell Harrena the cattle chief, Parnaka spoke as follows: ‘13 sheep and 5 portions issue to Bakatanna the horseman and his companions who feed (?) the horses and mules of the king and of the princes (at) Karakušan. (It?) has been changed (?). 135 men, 1 sheep received by each 10 men.’

Month 7, year 19, this sealed document was delivered. Karkiš wrote (it). Maraza communicated the message.

6 (BAR of grain), delivered (in accordance with) a sealed document of Iršena, Masana the hamarnabattiš received, and 1 young horse, maintained at Hadaran consumed (it as) rations. (For) 1 month, the 5th, (in) the 19th year; it consumed 2 QA daily…

63 (BAR of grain), delivered (in accordance with) a sealed document of Iršena, Kunsuš the horseman, (for whom) Yaumanizza (does) the apportioning, received, and I ber (mature?) horse, maintained at Hadaran, consumed (it as) rations. For 7 months, from the 3rd through the 9th, in the 19th year, it consumed 3 QA daily.

The texts also name individuals who safeguarded the welfare of the royal horses as well as groups of court officials serving as Masters of the Horse, as it were (PF1942, PF1943, PF1947, PF1948), and show that these men operated within a hierarchical system and could be paid well beyond the average ration-rate and could enjoy a diet of regular meat. This suggests a high-rank at court for Masters of the Horse.

While there are no surviving monumental artistic representations of horses and riders in Achaemenid art, textual evidence suggests that equine statues of horses with riders were commissioned for and by royalty and nobility:

From Arshama to Nakhthor, Kenzasirma, and his associates. Concerning: Hinzanay, a sculptor and a servant of mine, whom Bagasrava brought to Susa. Issue rations to him and his household, the same as those given to the other artisans on my staff. He is to make a statue of a horseman […]. They should be […]. And he is to make a statue of a horse with its rider, just as he did previously for me, and other statues. Have them sent to me just as soon as you can!

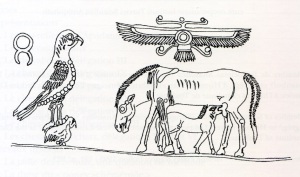

Small scale representations of horses and cavalry figures survive in terracotta and metalic figurines, and representations on gems, coins, and textiles. The Persepolis reliefs show riderless horses regularly: of the twenty-three tribute delegations appearing on the Apadana staircases, seven present horses as part of their gifts (Medes, Armenians, Cappadocians, two groups of Sakas, Sagartians, and Thracians) and there are also depictions of horse-drawn chariots conveyed by Syrians and Libyans. In addition, the Great King’s personal Nisaean mounts are depicted along with his chariot (and the chariot belonging to the Crown Prince). In the royal chariot the Great King obviously took on a majestic appearance, ‘outstanding amongst the rest’ (Curtius Rufus 4. 1.1) but, as Briant makes clear, ‘the royal horses and chariot do not appear on the Persepolis reliefs simply for decoration. The royal chariot obviously carried ideological weight and the vehicle was clearly part of the ‘royal insignia’’.

As an obvious symbol of status and wealth, horses were closely connected to royal and courtly ideology and to the model warrior image (XPl §2h):

As a horseman I am a good horseman. As a bowman I am a good bowman, both on foot and on horseback. As a spearman I am a good spearman, both on foot and on horseback

But as a mark of conspicuous leisure, horses played a dominant role in the aristocratic pastimes of hunting and racing (Xenophon, Cyropaedia 8. 3. 25, 33; see further Herodotus 7. 196). Favourite horses could lead a pampered existence (Herodotus 9.70).

A companion in life, the horse also played its role in the ceremonies of death and with the passing of a king or noble, his horse was included in the mourning procession with its mane cropped short (Herodotus 9. 24; Curtius Rufus 10. 5.17). The horse played a noteworthy role in Achaemenid rituals and beliefs and just as kings were mounted high on horse-drawn chariots, so Ahuramazda and other deities had similar modes of transportation (Herodotus 7. 40; Arrian, Anabasis 2. 11, 3. 15; Xenophon, Cyropaedia 8. 3.12). Moreover, just as the finest present to give a Persian was a horse (Xenophon, Anabasis 1.2.27), so were the gods honoured with equine gifts such as the white horses which were sacrificed to the sun and to the waters (Herodotus 1. 216, 7. 113; 1. 189; Xenophon, Cyropaedia 8. 3.11-12; Anabasis 4. 5.35; Pausanias 3. 20.4; Strabo, Geography 11. 13.7; 11. 13.8, 14.9), both rituals being widely practiced amongst Indo-European peoples (Clutton-Brock 1992; Kelekna 2009). As founder of the Empire, Cyrus II was honoured with a horse sacrificed to his soul every month (Arrian, Anabasis 6. 29.7.). Moreover, the infamous tale recounted by Herodotus (3.85) of how Darius I acquired his kingdom through a trick involving the neighing of his horse is, in all probability, a Greek misunderstanding of the Iranian practice of hippomancy, or divination through the behaviour of horses (see also Ctesias F13 §17), demonstrating the deep-set importance of the horse as a hallowed species in the Iranian consciousness.

خوب میشد زبان فارسی میشد بتونیم مطالب رو بخونیم لطفا اگه میشه به زبان فارسی ترجمه کنید .

ممنون

من متاسفم اما من فارسی نوشتن نیست

Hello. I’m a 16 year old persian and i just saw you on a channel. It’s the biggest honor for me to hear a foreiger is intrested in our history. Unfortunetly my english is not that good to understad all of it, but i wish so many foreigners check your amazing website out. I feel proud! Wow! I think right now you know about my history more than myself haha. GoodLuck with your job. 😉

Thank you very much for your kind comments. And your English is very good!!

I love the history and people of Iran and I am happy that I am able to teach Persian history at Edinburgh University.

Please tell your friends about my blog.

Very best wishes,

Lloyd

Hi dear, i want to ask you something, can you write about arabs attack to iran?

Hello Hamed,

I’m sorry but that is not my area of expertise. My work tends to focus on the Achaemenid period, so many, many centuries before the Arab conquests.

Very best wishes,

Lloyd

Thank you.

after I saw you in manoto tv

Very interesting! Liked your website very much. Happy to see that you are so interested in history of Iran and actually you like Iran. I don’t know whether you’ve visited other places and cities than Shiraz, Isfahan and Shush or not; i recommend you to have a trip to Kermanshah where you would enjoy visiting historical places such as Bisotun and TaaghBostaan. i’m waiting for your new posts 🙂

I’ve been luck enough to travel to Kermanshah, yes. I loved it there. But I have never visited the Caspian or Tabrix, Gorgan or Mashad. One day I will, God willing.

Lloyd

I’m very happy to see a English is interested in our country and history.

But I think it’s better that you add Persian language in your website

Thank you for everything.

I wish that I could translate everything into Persian – but it is a question of time and experience, I’m sorry.

hi lioyd.How are you?

Its a very interesting blog about Iran.

I’ll be happy when see a human like you.

Thank you… because you hold our history of Iran

And its a very Beauty

I tell my friends about your blog

موفق باشید

Hi.

thanks for making this website and i hope u will continue new subjects.

my major is studying on ancient iran and i use your themes.

thanks again.

Thank you Ali! That is a very kind comment. I’m very happy that you find my blog useful. Tell your friends to visit it too!

Hi Lloyd,

Great post. So do you think when the Parthian / Persian ‘wise men’ went to visit the Messiah in Jerusalem, they rode on horses, not camels as all the Christmas cards would have us believe?

Many thanks

OOOoo I’m not sure I can answer that with certainty, but I can say a few things on camels:

Camels do not figure quite so prominently in the sources but they are nonetheless attested often enough to prove their worth to the Persians and in fact, the Old Persian word for camel, uša or uštra, often occurs as a component in personal names (most markedly Zarathuštra, ‘he who manages camels’). Images of Bactrian camels are unmistakable and copious, for they are included in the representations of several delegations from north-east¬ern Iran at Persepolis whereas single-humped dromedaries are depicted only with the Arab delegation. Swift dromedary camels were important sources of meat, milk, and hair and while they were used as pack animals (Herodotus 1. 80) they were not engaged in heavy hauling. In fact, none of the Persepolis camels are portrayed as draft animals, but post-Achaemenid period sources give explicit references to camel-drawn carts (Strabo 15. 1.43) and one Achaemenid seal-image shows the Great King in a chariot pulled by a team of dromedaries. Both species of camels were used by the Persian cavalry and we know that Darius I certainly employed camel troops (ušabari) in his campaign against the rebellious Babylonians (DB I §18). Large herds of camels belonging to the king are attested in the Persepolis texts being driven back and forth between Persepolis and Susa and Greek artists sometimes depict the Great King riding a camel. One small seal illustrates the Great King spearing a lion while seated on a dromedary, suggesting that camels could be used in the hunt too. Occasionally a much-beloved camel is attested in the sources – like the lucky one stabled at Gaugamela by Darius I (Strabo 16. 1.3).

So – the mode of transport for the Wise Men…? The jury is still out!!

Very best wishes,

Lloyd

Thank you ,but : “Persian horseman depicted on a felt saddlecloth from Pazyrik, fifth century BCE”…. is not Persian but Scythian, and bounding tail of a horses is Turkic. Scythians are Turkic tribe….best wishes 🙂 …http://s155239215.onlinehome.us/turkic/27_Scythians/Contents_Scythians_En.htm

and the Pazyryk : “Structure of the control region of the mtDNA isolated form three representatives of Pazyryk Culture of Gorny Altai (IV-II century BC), one of the central cultures in the Scythian-Siberian world, was analyzed by molecular genetic techniques.”…http://s155239215.onlinehome.us/turkic/64_Pazyryk/Pazyryk_gensEn.html